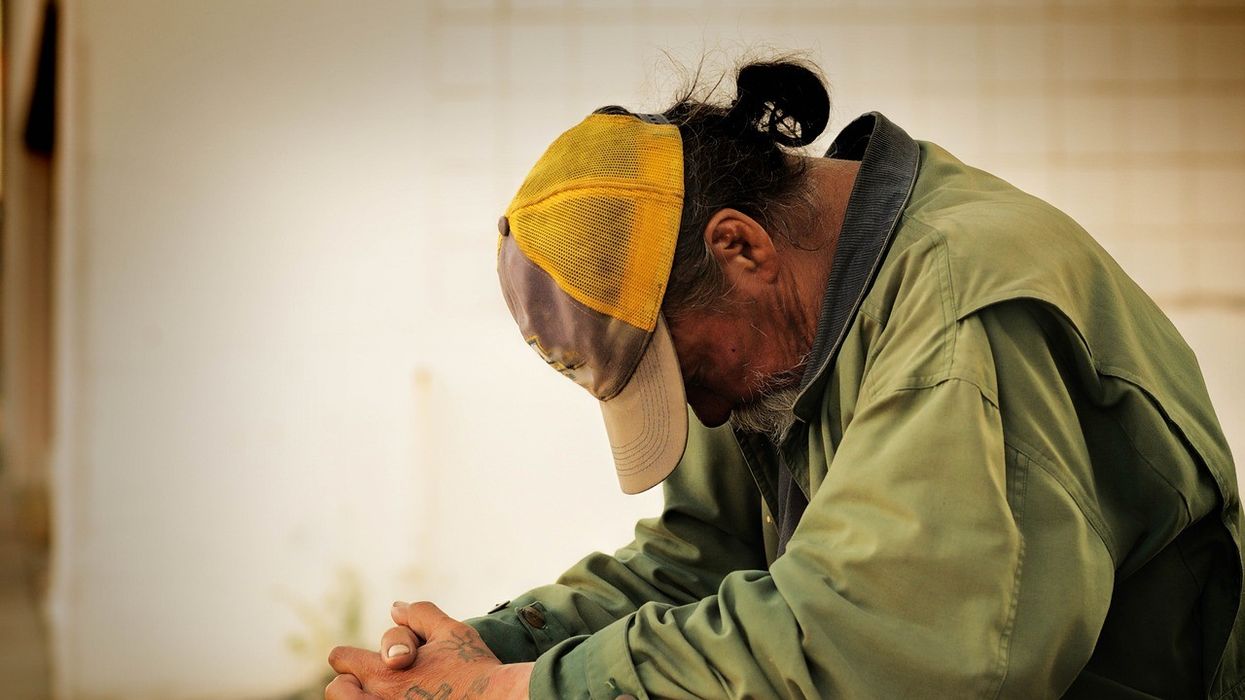

In 2018, a total of 23 men died in Toronto’s homeless shelters. The average age of death was 56.5 years, which is nearly 25 years younger than the national average.

I'm a 54-year-old man who has been in the shelter system for eight months, after losing my home last June. To me, the statistic above evokes a palpable sense of foreboding. I'm all too aware of how easily I could slip even further through the cracks and in two and a half years, become one such statistic.

But I am not the only one. The cracks are widening, and as my fellow shelter client observed, “…the cracks are not only widening, they've become glaring chasms of [housing] inequality”.

The last time I was homeless was between June of 2004 and June of 2005. Back then, the typical shelter clientele base was composed mostly of people with significant addiction issues.

READ: 3 Ways To Prevent Homelessness Instead Of Just Reacting To It

Now, because of the housing crisis, the homeless demographic has shifted dramatically. Far more low-income and working-class people are living in the shelters, as are a growing number of people with physical and psychological disabilities, and fairly severe medical conditions.

Most of us are here because of a lack of affordable housing or inadequate housing supports. Collectively, we constitute the human fallout of housing insecurity - or to put it another way - the collateral damage of soaring rent rates in a ‘world class city’.

Some clients exhibit concurrent symptoms akin to Autistic Spectrum Disorder, Schizophrenia and Depression. Others are visually and hearing impaired. And some suffer from chronic and incurable pulmonary diseases that put them at risk of infection in the overcrowded shelter system where H1N1, pneumonia and tuberculosis outbreaks are common.

READ: The Four Catch 22’s Of Housing Insecurity For Low-Income Torontonians

As the registered nurse and client caseworker at Native Men's Residence, Patricia Stephens is acutely aware of the changing population, and their evolving needs.

“In the two years since I became a nurse in the shelter,” recalls Stephens, “I’ve seen seniors, people in wheelchairs and walkers, people on dialysis and people coming here despite being banned from all long term care facilities for assaulting staff. And that’s all quite aside from the overdoses.”

I too have witnessed more assaults this time around, perpetrated against shelter staff and clients. Some clients are angry, but can't diagnose nor articulate why. They lash out, partly in anger, but mostly in fear and in pain.

The number of clients at the shelter has also increased by almost 40 per cent. In 2005, there were a total of fifty beds, numbering two to three clients per room. Today, there are now sixty-nine beds in the shelter, averaging four clients per room.

READ: Toronto Has A New Hospice That Offers Palliative Care To The Homeless

Shelter staff and infrastructure are ill-equipped to adequately serve this increased clientele, let alone one with such a diverse range of needs and challenges.

Charlie, a resident of the shelter, is a hearing impaired Inuit man in his mid-twenties. During a recent housing workshop conducted by the housing worker, there was, as usual, no ASL interpreter present. I glanced over at Charlie to see if he was able to lip read well enough to understand the workshop. He wasn’t, and his eyes conveyed the frustration and loneliness of his circumstance.

Though many of these issues could be mitigated and, in some cases, resolved with appropriate housing supports, it is obvious that an immediate change is necessary within the shelter system itself.

Nurse Stephens suggests a smart first step: “Currently, nursing and other medical professionals in the shelter are considered ‘auxiliary’ rather than primary staff - they should be considered essential.”

Last August, I attended an affordable housing rally in Parkdale. While wending my way through the column of protesters, I met two young women holding up a placard that read ‘SAFE HOMES SAVE LIVES!’ Having heard that I was recently homeless and what their slogan meant to me, they approached me after the rally and presented the placard as a gift - a gift which I felt honoured to receive.

But given the average age of the men who died in the shelter system last year, that slogan now hits home with near prophetic poignancy: “Safe homes do, in fact, save lives. Shelters, on the other hand, can potentially shorten them.