Just when you thought you’d heard everything about Toronto’s frenzied housing lust — the much-sketched sagas of supply and demand — we get word that the real estate for the dead sits at an even bigger premium.

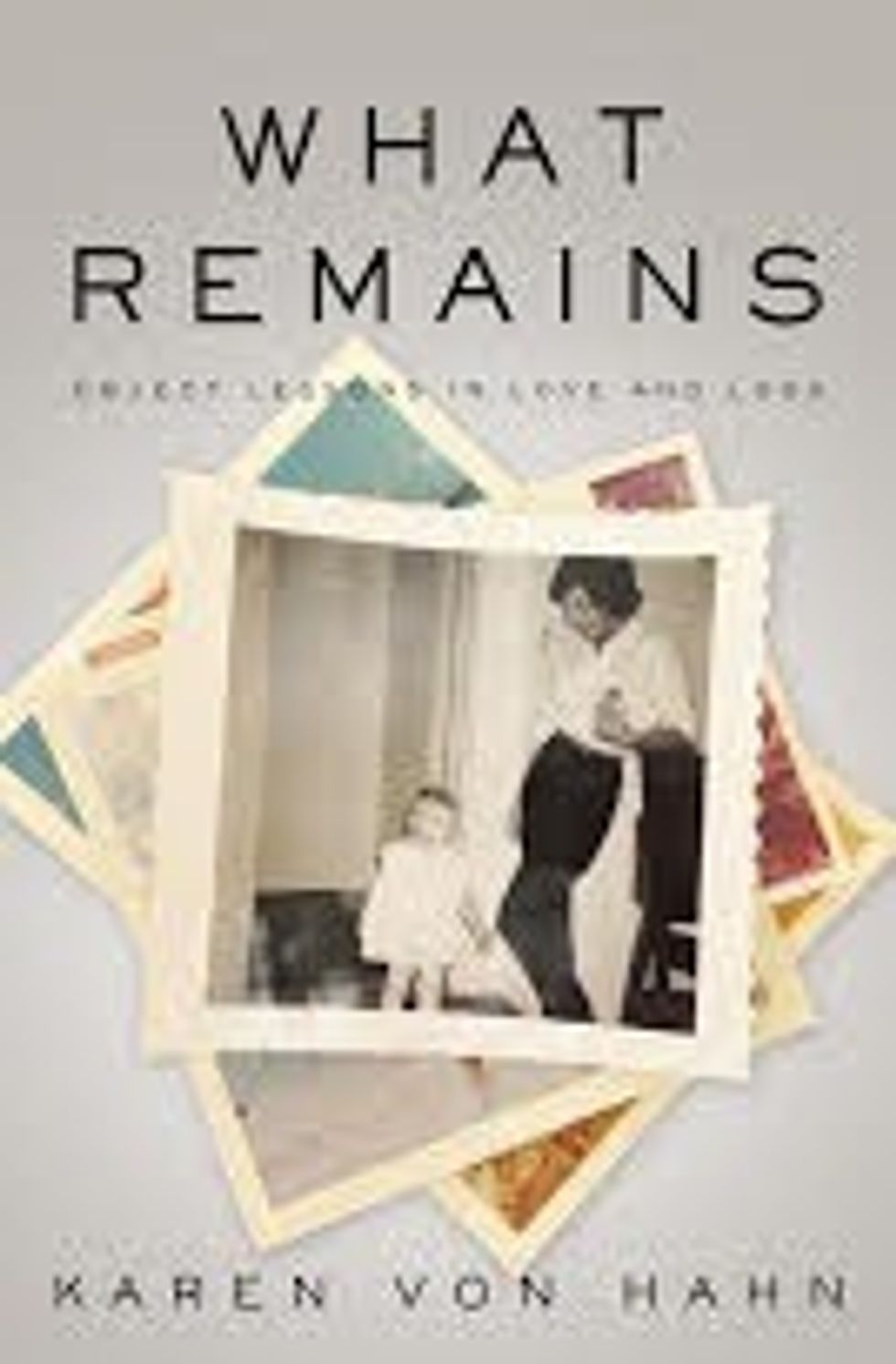

Dishing on her family’s quest to get “possibly the last remaining spot” in the posher, greener part of Mount Pleasant Cemetery, Toronto tastemaker Karen von Hahn gives a pretty droll recounting in her just-out memoir, What Re

“I couldn’t not write about it,” von Hahn exclaimed at her lively book launch, held the other week at the hotspot Leña on Yonge Street.

Long story shortish: after her mom, Susan, died, there was no question in the family’s mind that “her final resting place was not going to be the grim and treeless Jewish cemetery" up in the nouveau environs of North York. For her, after all, Toronto proper, “comprised the area between Annex and Rosedale,” with only the occasional dash south of Bloor to a restaurant, gala or Toronto International Film Festival event.

(Ossington? What’s that?)

Heeding to what would have been her wishes, the family — less than 24 hours after her passing — were racing to Mount Pleasant to see if they could find a spot, given that Mount Pleasant near Moore Avenue is where the “grand old Canadian families are buried, under the old heritage elms and willows in beautiful stone crypts.” It is, after all, where the Eatons lay in perpetuity, in a neo-Georgian stone temple, as do the Masseys, shrouded in designer ivy.

“In post-colonial Canada,” alas, “class snobbery is still so ingrained, it outlasts even death,” von Hahn writes in What Remains. “Officially, Mount Pleasant doesn’t discriminate — in reflection of the diverse, multicultural city it has served, there are also rows of tombstones with “ethnic” names, many engraved in Chinese characters.”

Grand family crypts

But ... but ... “These tombstones of the city’s later arrivals tend to be housed in the newer, less established grounds of the cemetery, which, in the landscaping expression of the social hierarchy, just happens to sit in the treeless field behind the grand family crypts on the hilltop.”

In other words: location, location, location.

For von Hahn’s mummy — who was a convert to Judaism, and somewhat self-invented — things didn’t look good.

And, yet, somehow, someway, someone knew someone who knew someone, no doubt — and Susan was also able to nab a primo spot, after all. A result that, as von Hahn elaborates, spurred no shortage of oohs and aahs from her “establishment friends and acquaintances,” many of whom could not talk about anything else when they heard.

After a bit of a scramble to get a rabbi there to perform the rites — “Mount Cemetery doesn’t have one on its Rolodex,” the writer confirms — Susan got her way. On a cloudless day in March, the rabbi-for-hire performed the last rites as she was lowered beneath the long branches of a beautiful old silver maple.