What comes first, gentrification, or high home prices? Does the young urban professional couple follow the Starbucks, or does the Starbucks follow them?

Hyder Owainati, marketing communications manager at TheRedPin.com Brokerage, says it’s a bit of a chicken-or-egg argument. While they influence each other, an unprecedented housing demand in the GTA means that developers are eager to launch shiny new communities — and rocketing prices are also pushing populations into untapped areas.

“In cases such as Liberty Village or the upcoming master-planned condo community of River City, gentrification comes first,” Owainati says.

“Developers are strategically creating new communities in previously industrial — and somewhat neglected areas — and creating new dynamic communities in their place. It’s very much a planned and meticulous process.

“On the other end of the equation, prices can be the main force driving gentrification,” he says. “As home values keep driving up in prime areas, buyers are being pushed further outwards — rejuvenating new neighbourhoods as they branch out.”

A particularly hot real estate market, however, shifts the assumed potency of gentrification — now, almost any property in almost any neighbourhood is considered valuable in Toronto. But, as Owainati points out, not all price jumps are created equal.

“While the city is in the midst of a fierce seller’s market, gentrification is pushing prices higher in some neighbourhoods more than others,” he says.

“Areas such as Bayview have seen monumental price jumps — thanks in large part to Bayview Village Shopping Centre and the Sheppard subway extension,” he continues. “South Riverdale is also seeing a push in prices, due to a slew of new condos popping around — the restoration of famed Broadview Hotel and the proposed 60-acre commercial site dubbed East Harbour.”

‘A PERIOD OF ENORMOUS TRANSFORMATION’

Standing shoulder-to-shoulder with relatively comparable, gentrifying cities in other countries, Toronto is unique.

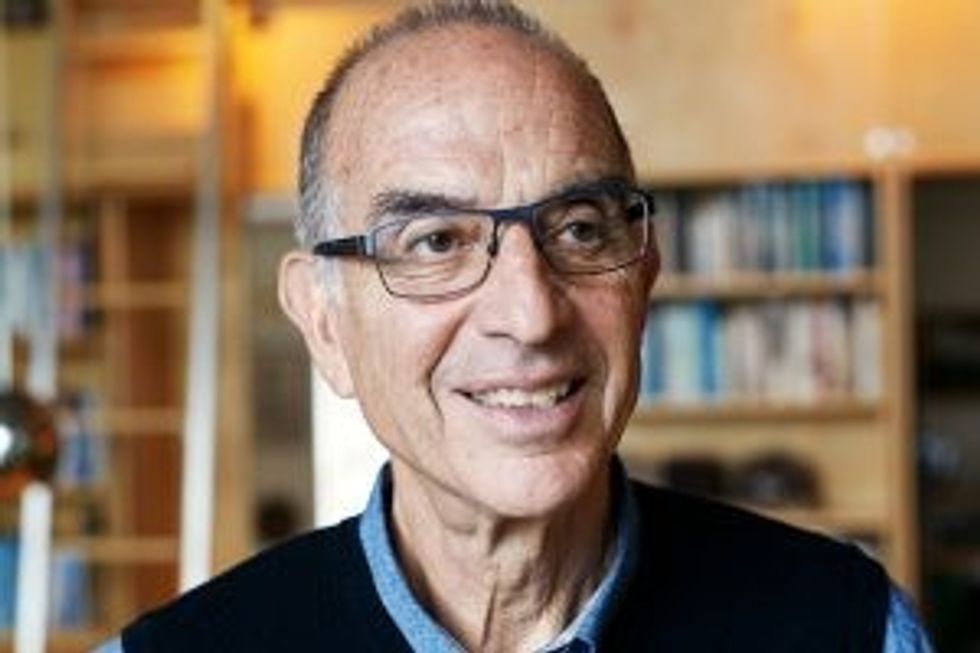

Ken Greenberg would know. He’s dedicated 40-plus years of his life’s work to the rejuvenation of downtowns, waterfronts and neighbourhoods, and played pivotal roles in regional growth management and new community planning.

The award-winning urban designer, teacher and writer — and former director of urban design and architecture for the City of Toronto and current principal of Greenberg Consultants — has lent his expertise to such cities as Amsterdam, New York, Boston, Montreal, Ottawa, Edmonton, Calgary, St. Louis, Washington, D.C., Paris and Detroit, among others.

“What distinguishes Toronto is that, in some cities, this (gentrification) phenomenon is very concentrated in a few areas and produces what’s sometimes called ‘cataclysmic change,’” he says. “This forces all the residents out, as new people come in. Because the rise in property values is so precipitous, and so concentrated, it has a devastating effect.

“So I’d say (gentrification) is happening very significantly in Toronto, but I’d say it’s happening in a more dispersed pattern. It’s a much more spread-out kind of phenomenon and, certainly compared to a lot of U.S. cities, it’s less concentrated.”

The features that make Toronto’s gentrifying patterns distinct are both tangible and intangible, Greenberg says. On the one hand, our absence of freeways encouraged families to stay — on the other, the race and class divisions in Canada aren’t as stark as those down south.

“We stopped building expressways early in the game, whereas if you compare with U.S. cities, a lot of the inner-city neighbourhoods were literally disemboweled by expressways,” he says. “We didn’t have as much as that in Canada. We didn’t have a big exodus from the city to the suburbs, which resulted in the cities in the older neighbourhoods being really low-income, and really vulnerable to gentrification. In Toronto, a lot more people stayed.

“And I also think we don’t have the fear factor in Toronto,” he adds. “There’s hardly anywhere in Toronto where people don’t feel comfortable being.

“Whereas, in many other cities, the reason gentrification is so concentrated is that there are a lot of areas in the city that people just don’t feel comfortable in — for a whole variety of reasons, but a lot of it has to do with race and class, which has not afflicted us as much.”

‘GETTING BACK ON THEIR FEET’

So what is gentrification? Is it a condo developer buying an old parking lot or, as often-quipped, the Starbucks popping up on the corner? Is it when average incomes in a certain neighbourhood reach “middle class”? When expensive strollers crowd the sidewalk?

At the highest level, Greenberg sees gentrification as a cultural shift in values and lifestyles, and the subsequent desirability of city life. It’s when the Canadian dream is no longer comprised of highways, suburbs and malls, and two cars in every driveway.

“When we say gentrification, what we’re really talking about is a phenomenon which has to do with a new embrace of the city by large numbers of people,” he says. “People who want to move into neighbourhoods that are walkable, that have transit, local shopping — and that’s happening across North America.

“And I think right now we’re in a period of enormous transformation, as we make a shift that is as profound as the one that occurred after World War II, when everybody got in their cars — now, to people getting back on their feet.”

Younger generations and empty nesters alike value lifestyle and their time — they don’t want to sit in traffic, Greenberg says. Given the choice, Torontonians generally want to be closer to where they work, study and play. Condo developers are learning that, if you build it, they will come.

“That’s really at the root of a lot of this — gentrification, rejuvenation, rediscovery of former industrial lands, warehouse districts, waterfronts,” he says. “You can’t stop people from wanting to live in cities.”

The downside, of course, is that it’s not a choice for everyone. Many can’t afford to live in the city — urban rent is climbing and there’s a drought in new supply. The working class are being pushed out.

So while Toronto should be celebrating its popularity, it has to remember its core identity and joie de vivre — and what we’re known for, especially to neighbours down south. We’re supposed to be a city of inclusivity.

“I think things that public policy can do is accept the fact that this is a very powerful force and that we have to develop policies to provide more affordable housing,” Greenberg says.

“So things like inclusionary zoning, and creating more forms of housing that are not just subject to private market forces, are absolutely critical — unless we want to have a really polarized society.”